A Brief History of Risk (IV) Von Mover and the Curve of the Gods

Author: Ilidhan, Created: 2017-01-04 10:17:13, Updated: 2017-01-04 10:19:14Younger than 4 years old, Younger than 4 years old, Younger than 5 years old, Younger than 5 years old, Younger than 5 years old, Younger than 5 years old, Younger than 5 years old, Younger than 6 years old, Younger than 6 years old, Younger than 6 years old, Younger than 6 years old, Younger than 7 years old, Younger than 7 years old, Younger than 7 years old, Younger than 7 years old, Younger than 7 years old

The previous issue stated that Jacob Bernoulli had not published his book on probability theory at the time of his death. The task of compiling his manuscript was entrusted to his nephew Nicholas II Bernoulli (that early-born genius). Nicholas, after completing his uncle's wishes, began to want to study again the level of deviation from the true probability, having already determined the number of observations. Abraham de Moivre has been translated into many places as Meremivir, but after seeing his portrait, I am not a big fan of the latter translation. This invitation could have fulfilled a number of theories that would have been passed on to the next generation, but Abraham de Moivre refused, and he refused because he felt he did not have enough flood power.

-

What is it? In fact, Baumov was only a few years younger than Jacob Bernoulli, and his entire life could actually be described in one novel, which was The Disastrous World of Newton. France was then a country with a fanatical Catholic atmosphere, and Baumov was, coincidentally or not, a Protestant. Later, King Louis XIV of France issued a decree declaring that Protestants in the country were inferior citizens, and children had to convert to Protestantism, which essentially made Protestantism a cult in France, and Baumov spent two more years in prison.

In 1711, Von Mover published a book on the measurement of fortune, which, if it had been published at the time, would have included Newton's recommendation: "Ask Mr. Von Mover, he knows more about this than I do".

Unfortunately, it wasn't at the time, so Kimmoff couldn't even carry his leg to raise too much royalties.

You should also remember the question we asked in the previous post (Risk Story 3): Major Bernoulli, for 5,000 pebbles in a cage, we can do 25,500 grabs to estimate the proportion of the total pebbles. But you should also find that 25,500 repeated grabs are too many, and it's not like throwing a stone out one by one.

Using calculus and Pascal's triangle methods, Baumhofer took a grouped sampling method. He assumed that each time 100 pebbles were taken out of the cage, the proportions of the black and white pebbles were recorded, then the stone was put back in, and then the same extraction was done. By this method, Baumhofer could tell you in advance the approximate deviation of the ratios you recorded from the true ratios, and how these ratios were distributed around their mean.

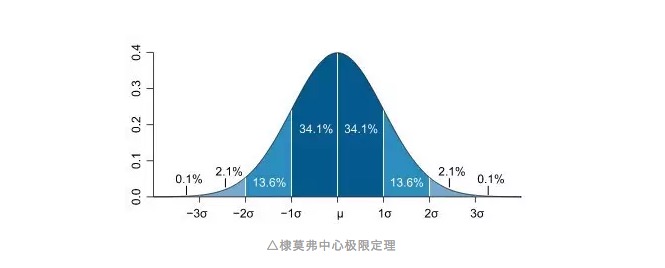

Is this statement familiar, or is it just a feeling in the mouth, or is it something you want to call out right away? Yes, this is the normal distribution that everyone is familiar with. The curve of the normal distribution is like a bell curve, with most of the observations clustered in the middle, close to the uniform values of all the observations, and then sloping symmetrically from the uniform values to both ends, and with the same number of uniform values at both ends.

In this way we can introduce the concept of standard deviation, which we have already mentioned in other articles in the Publications (Why Standard Deviation? Risk Measurement in God's Eyes). The standard deviation describes the degree of deviation of the observed value from the mean, or we understand it as the unit of deviation from the mean. For a normal distribution, the proportion of the pebbles we extract from a set of 100 will probably fall within 68% of the range of a standard deviation on either side of the mean, while the range of two standard deviations will probably comprise 95% of the observed value.

As a devout believer, Von Mover believed that bell curves were a product of God. In his view, by such measurements we can overcome uncertainty and thus conquer all risks, since all possible phenomena and their probabilities have been described on the curve, perhaps leading to so-called deviations from chance, but over time these deviations no longer affect the laws we conclude.

In the popular way of explaining the term, it is a disappointment that the phone number is occasionally unreachable, several times tried, always answers the question. In middle school, there is also a classic problem (hey, why I always use the problem in high school) is about the product pass rate. If for a batch of products, the industry standard considers that the waste rate does not exceed 0.1% is qualified, this means that we randomly select 10,000 from the product, if the waste does not exceed 10, it is qualified.

But most of the time, this question is meaningless to us. Because we may not know what the average waste rate of a product will be, how likely is it that a batch of our products will pass the test if the average waste rate is higher than the test standard? If 20,000 products are taken for testing, can the results of 10,000 products be directly used?

Translated from Chinese Quantitative Investment Society

- JSLint detects the syntax of JavaScript

- How partial equity impacts the average price of holdings

- Bitcoin exchange network error GetOrders: parameter error

- The template of the listing system triggers the design outline of ten items

- The technical gist of the shark system trading rules

- Template 3.0: Draw line class library

- Peak and slope

- The most profitable economist, writing papers and leading economist, Tom Maynard Keynes

- Template 3.2: Digital currency trading class library (integrated Cash, futures support OKCoin futures/BitVC)

- I'm sorry, but Gauss did a small job.

- A short history of risk (5) Bayes, a man who lives only in his textbooks

- A brilliant explanation for the alternative to stop loss

- 2.13 Common error messages, exchange API error codes, various problems encountered by digital currency robots!

- OkCoin China API error code requested

- The real volatility applied to the market basis of thinking about shushupengli trading ideas with pen

- 2.12 _D (()) Function and Timestamp

- python: Please be careful in these places.

- A synergistic understanding of intuition

- The hidden Markov model

- Interested in understanding the simplicity of Bayes